Character Last

In Why Your Favorite Entertainment Works, I shared an introduction to ECT, Entertainment Constant Theory.

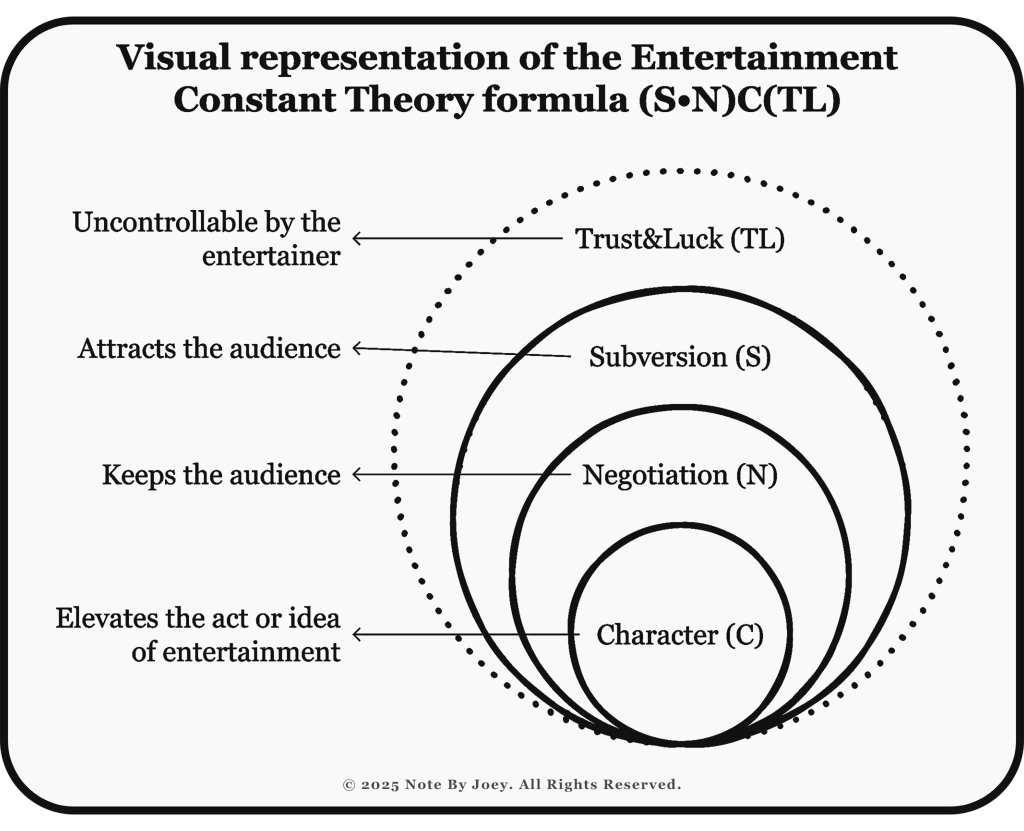

Entertainment’s effectiveness, to sum up, depend on three controllable, servicable constants by the entertainer—Subversion, Negotiation, and Character—which, when properly balanced with the uncontrollable variable of Trust&Luck by the audience, form a universal framework applicable to all forms of entertainment regardless of medium or genre.

Today, I want to focus on why most entertainment fails by lack of observing this theory. Its working formula is the following:

(S•N)C(TL)

Character, to sum up, bridges the entertainer (S•N) to the audience (TL), hence its placement.

Yet most entertainers fail because they prioritize Character, or characters, over the fundamental elements of Subversion and Negotiation, creating elaborately decorated but non-functional entertainment that cannot effectively engage the audience.

The Toilet Analogy

Think of entertainment like plumbing. Subversion is the handle—the audience reaches for it first. Negotiation comprises the pipes—the invisible but essential infrastructure that makes everything work.

Character, then, is merely how the toilet looks—important for overall impression, but useless if the handle or the pipes fail.

In list form:

- Subversion (S): the handle—what grabs attention first

- Negotiation (N): the pipes—what makes everything work

- Character (C): the appearance—important but not fundamental

- Trust&Luck (TL): everything outside the control of the entertainer

When the entertainer prioritizes Character over Subversion and Negotiation, they are decorating a toilet that may not flush, and submitting themselves to whatever may come of the audience (again, Trust&Luck).

And this mistake, of prioritizing Character, is just as evident in multi-million dollar projects as it is at your local open mic.

Where We See (and Hear) This

Film Entertainment

Remember the failed “Dark Universe” with its star-studded cast photo released before a single successful film? Or expensive video games with incredible pre-rendered, cinematic trailers, but the game itself winds up not compelling to gamers? These are Character-first approaches.

Studios announce casting decisions months before having solid scripts, hence reshoots are the norm. They debate over who, before why the audience should be compelled. This happens because they view Subversion and Negotiation as afterthoughts to the material, when, as my first article on ECT argues, the material doesn’t matter. What matters is the balancing act of these constants by the entertainer for the audience.

Stand-Up Entertainment

Many comedians develop a persona, then stop evolving their jokes. They find a style that works—the intense confessor, the observational everyman—and milk it dry.

They rarely recognize when their service to Subversion has grown stale. Instead, they double down, or blame the audience. What began as fresh becomes formulaic because they prioritized Character and run with it, without knowing rightly how they got there.

The aged comedy special, likewise, by their nature, eventually becomes ineffective at compelling the audience. The value of Trust&Luck, accordingly, is reduced, contributing to an even lower total value by the entertainment for the audience.

Music Entertainment

The music industry, though an auditory medium, suffers from this Character-first misconception just the same. Artists change their look dramatically while their sound barely evolves. They generate buzz, but rarely sustain relevance.

When Radiohead released “Kid A,” they transformed both their sound and aesthetic together. When Taylor Swift moved from country to pop, both her music and persona evolved in tandem. These artists use Character to amplify innovation, not replace it.

Why The Misconception Persists

This backwards approach persists for three main reasons besides merely not knowing of this formula’s existence:

- Character is visible – It’s easier to see and discuss Character than Subversion or Negotiation

- Character gets rewarded – The industry celebrates Character transformations more than substantive innovations

- Character is less work – Servicing the audience through empathy can be hard for even the already successful entertainer to grasp or want to consciously do

This creates a system where entertainers invest in what’s visible, safe, and easy for them—even when it’s not what actually engages or compels the audience.

Fixing the Formula

The solution isn’t abandoning Character—it’s putting it in its proper place:

- Start with Subversion: Find ideas that naturally excite or surprise you

- Develop Negotiation: Balance authority and empathy in presenting these ideas

- Consider Character: Choose a grouping of ideas that enhances this foundation

- Submit to Trust&Luck: Now it’s in the hands of the audience to say whether there is value in your act or idea of entertainment

When entertainment fails, most creators choose to blame their Character or, worse, the audience. Instead, they should examine their Subversion and Negotiation—the elements within their control and that audiences actually respond to and can be compelled by.

Entertainment, in summary, isn’t magic or entirely luck—it’s a craft with clear components working in sequence, to earn the trust of the audience. When we recognize and honor this sequence, the entertainer stands a chance to create work that compels the audience, despite the uncontrollable variable of Trust&Luck.

In our next essay, we’ll explore how authentic Character emerges organically through successful Subversion and Negotiation over time, rather than being artificially constructed—as perfectly demonstrated by Shane Gillis’s career trajectory.

Share Your Thoughts