The entertainer often struggles to examine acts or ideas of entertainment beyond an inclination or feeling. “You either got it or you don’t,” many say, too. Jerry Seinfeld attributes his joke writing skill to discipline. “Fuck education,” a comedian told me a year and a half ago.

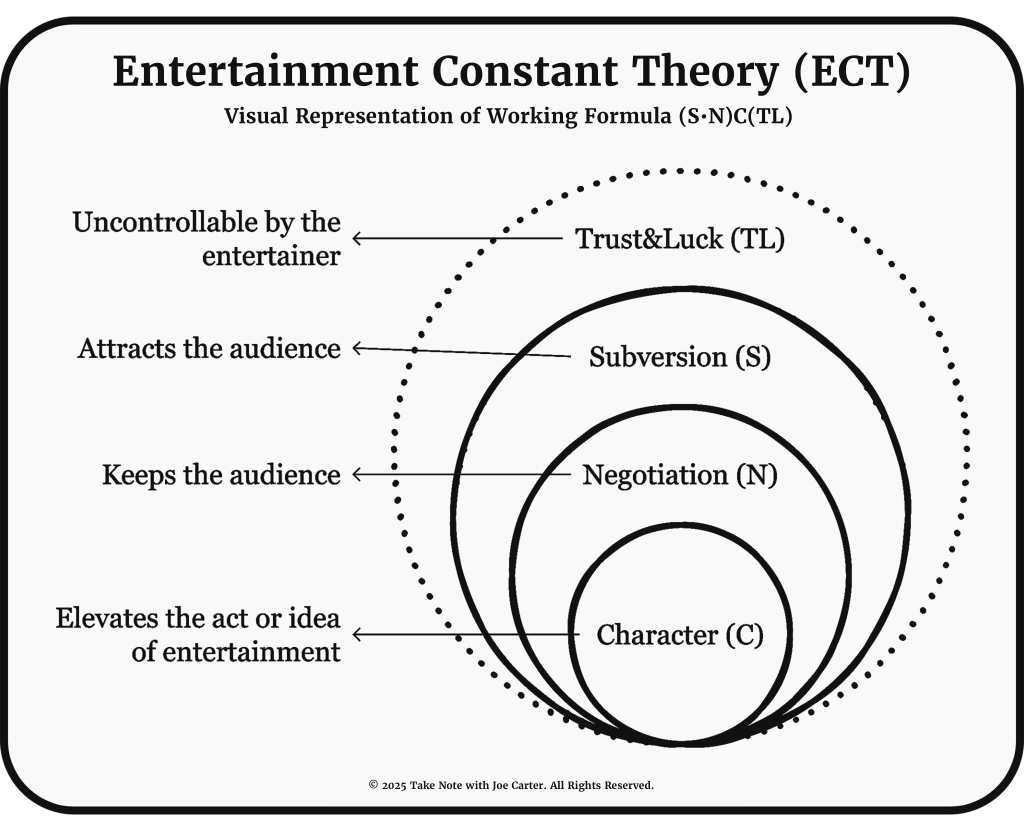

I’ve worked to develop a theory explaining the constants of entertainment. These constants can explain why and how the audience is compelled by the entertainer or entertainment.

I call it Entertainment Constant Theory (ECT).

The above perspectives miss what this theory fills in. Entertainment is a craft with identifiable, serviceable components. The entertainer services them, and ECT exposes them. Thus helping the entertainer increase their likelihood to compel or engage their client, the audience.

The Three Things The Entertainer Can Control

Entertainment requires more than just a hook to compel or engage the audience.

The audience wants more than distraction—there’s plenty of that everywhere. What they’re really seeking is an answer to the question everybody asks every minute of their waking day: “Why?”

Ideally, the audience says gladly why they’re watching or listening to something. Utterances of “this is so good” or “he/she is so funny” ensuing.

Because it’s the moment the toilet fails to flush, or the sink starts to leak, or the mirror falls off the wall that anyone starts saying to themselves, “Why?” So the audience walks — in search of a better plumber.

So what ensures the plumbing doesn’t break? What ensures the entertainer not only keeps their job, but excels in the craft?

What makes entertainment genuinely entertaining, or compelling?

The entertainer or entertainment creates value for the audience by occasionally getting down and dirty, and servicing the following three constants, what you will find in any and all form of entertainment.

S: Subversion

Subversion is at the root of all entertainment. It must be constantly serviced by the entertainer (musician, comedian) or entertainment (film, song).

The audience simply will leave, swipe away, or mentally check out should the entertainment fail to subvert their expectations.

But subversion alone is like bringing a knife to a gunfight—likely stupid, incredibly easy. That’s why the entertainer or entertainment must service the following two elements, also.

N: Negotiation

If subversion attracts audiences, negotiation keeps them in their seats.

Referring to Entertainment Constant Theory’s formula, (S•N)C, you see that N can heavily influence the outcome of any given idea of entertainment.

Negotiation combines two essential ingredients:

- Authority: The entertainment demonstrates skill or credibility to the audience

- Empathy: The entertainment demonstrates an effort to understand or consider the audience

Ever notice how, after telling a joke that may have fallen flat, people quickly explain it? This is negotiating. They may inject authority: “I’ve been in the business for thirty years and they’re all like that; trust me.” Or they show empathy: “Sorry, you probably think I’m terrible for saying that,” with perhaps an added, “That’s not what I really mean, but do you know what I mean?”

Boo.

C: Character

Character acts like a bandage that holds subversion and negotiation together.

In the formula (S•N)C, you’ll see character (C) is isolated.

The constant of character in entertainment constant theory is the difference between Theo Von and any other talented comedian. Or, for (extreme) instance, the Beatles and any other talented musician. Character, in summary, elevates Subversion and Negotiation that would otherwise seem less compelling to the audience.

Character is serviced best by entertainment when it’s (1) consistent, and (2) suitable. The following is those variables defined:

- Consistent: The entertainer or entertainment remains what it presents itself to be.

- Suitable: The entertainer or entertainment benefits the subversion and negotiation within itself through its choices.

We love what Kramer does because we know Kramer. Without that consistency—like if he suddenly joined a church and got a regular job—he wouldn’t be Kramer anymore. His character more than likely would not benefit the entertainment’s service toward subversion and negotiation.

Without strong character any amount of subversion or negotiation falls apart. A well-developed character can sustain itself through moments of criticism or doubt.

One last Seinfeld example: When Kramer caves first in that famous contest episode of Seinfeld, the audience erupts. If they hadn’t known his character so well, it might have been funny, but not nearly as impactful. Otherwise “Of course Kramer/Seinfeld would do that!” can’t be shouted.

Again, musical acts like the Beatles or Pink Floyd excel at character development. Their albums feature repeating patterns and stylistic references to other songs, creating, more than cohesive, consistent, suitable character, choices, for audiences to connect with and be compelled.

Also, Dave Chappelle can’t use Jim Gaffigan’s jokes verbatim, though he could make them work through his own character’s lens.

The Thing The Entertainment Can’t Control: TL

Okay, so to those still reading, I chose to subvert your expectations a little.

There is an added element to this formula that I’d like to share now, despite it not at all being in the entertainer or entertainment’s control or sphere of influence.

Trust&Luck is what the entertainment cannot service. Audience mood, cultural shifts, and more. It’s why jokes get old, or why people get cancelled—or propelled to success. TikTokers and podcast creators, indeed, wildly depend on Trust&Luck by this theory or formula.

They (TL) are combined into a single variable; when you gain or lose either one, the outcome is the same.

Should the entertainment be trusted, it’s lucky—it’ll earn more ticket sales, laughs, and applause. And should the entertainment lose the trust of the audience, that’s incredibly unlucky! It cannot be compelling, despite any of its service toward the other three variables.

Trust&Luck, finally, addresses the question many ask when I’ve first shared this formula: “So what if the audience just doesn’t like it?”

So what can entertainers do? Focus on the constants they can control—that’s 75% of the equation. As my college friends said, “C’s get degrees.”

One Last Surprise

Here’s what’s most shocking by this insight: The material itself doesn’t matter.

What matters is the balancing act—servicing subversion, negotiation, and character—and how that connects with Trust&Luck. Then, repeat, whether it’s testing jokes at an open mic or feeding content to algorithms.

What’s Coming Next

I’m organizing my complete theory using NotebookLM, and may release a few more detailed articles. Stay tuned and let me know your thoughts.

What patterns do you see in your favorite entertainment? Share your thoughts with me.

Share Your Thoughts